Candy Read online

Page 2

Then one day Lingzi didn’t come to school. And from then on, her seat remained empty. The rumor was that she had violent tendencies. Her parents had had to tie her up with rope and take her to a mental hospital.

Everyone started saying that Lingzi had “gone crazy.” I started eating chocolate with a vengeance, and that was the beginning of my bad habit of bingeing on chocolate whenever I’m anxious or upset. Even today, eleven years later, I haven’t been able to break this habit, with the result that I have a very serious blood sugar problem.

I sneaked into the hospital to see her. One Saturday afternoon, wearing a red waterproof sweat suit, I slipped in through the chain-link fence of the mental hospital. In truth, I’m sure I could have used the main entrance. Although it was winter, I brought Lingzi her favorite Baby-Doll brand ice cream, along with some preserved olives and salty dried plums. I sat compulsively eating my chocolates while she ate her ice cream and sweet olives. All of the other patients on the ward were adults. I did most of the talking, and whenever I finished saying something, no matter what the subject was, Lingzi would laugh. Lingzi had a clear, musical laugh, just like bells ringing. But on this day her laughter simply struck me as weird.

What did Lingzi talk about? She kept repeating the same thing over and over: The drugs they give you in this hospital make you fat. Really, really fat.

Sometime later I heard that Lingzi had left the hospital. Her parents made a series of pleas to the school, asking the teachers to inform everyone that Lingzi was not being allowed any visitors.

One rainy afternoon, the news of Lingzi’s death reached our school. People said that her parents had gone out one day, and a boy had taken advantage of their absence. He had brought Lingzi a bouquet of fresh flowers. This was 1986, and there were only two flower stands in all of Shanghai, both newly opened. That night, Lingzi slashed her wrists in the bathroom of her family’s apartment. People said that she died standing.

This terrible event hastened my deterioration into a “problem child.”

I quit trusting anything that anyone told me. Aside from the food that I put into my mouth, there was nothing I believed in. I had lost faith in everything. I was only sixteen, but my life was over. Fucking over.

Strange days overtook me, and I grew idle. I let myself go, feeling that I had more time on my hands than I knew what to do with. Indolence made my voice increasingly gravelly. I started to explore my body, either in front of the mirror or at my desk. I had no desire to understand it—I only wanted to experience it.

Facing the mirror and looking at myself, I saw my own desire in all its unfamiliarity. When I secretly pressed my sex up against the cold corner of my desk, I sometimes felt a pleasurable spasm. Just as it had been the first time, my early experiences of this “joy” were often beyond my control.

This was the beginning of my wasted youth. After that winter, Lingzi’s lilting laughter would constantly trail behind me, pursuing me as I fled headlong into a boundless darkness.

C

There was only one teacher I liked at my school. She was very young, and tall and slender. She liked to wear dark glasses, and from day to day she always had the same quiet, unhappy air about her. She taught my class just once, and before starting the lesson, she read us a poem, “I Am a Willful Child,” by the underground poet Gu Cheng. No teacher had ever done anything like this before. Those ten minutes were the only moment of transcendence of my entire high school career—the spirituality of the teacher’s chaste gaze, us listening to the poem, the classroom in the sunlight. A perfect day, a beautiful dream. Over the years, memories of that day have often come back to me, and they have never lost the power to affect me deeply. It was as though I had never been truly moved by anything until that moment.

The term that Lingzi committed suicide I dropped out of school, the only student who had ever left voluntarily. I had set myself free. I was hoping to find some other way to get into university, since I still wanted to go to college someday. But you can’t get into college without graduating from high school.

I came to a conclusion: there was too much bullshit in my life. I didn’t want anyone to bullshit me anymore, and I wasn’t going to bullshit anyone else again either.

After I left school, I was introduced to a black-market booking agent, and that was how I fell into my brief career as a small-time nightclub singer. I love to sing—it gives me a kind of release. I would stand onstage, dressed up in ridiculous 1980s Taiwan-style outfits, making a big show of acting heartbroken. In those days I drew my eyebrows thick and dark, and I liked the plaintive and torchy Taiwan pop singers Su Rui and Wa Wa.

There was a dancer in our band who was even younger than I was. He had a clear gaze and was rather excitable. The two of us were very close and used to hang out together smoking Phoenix cigarettes. He went by the nickname Bug, but he was actually quite large and didn’t bear the slightest resemblance to a little bug. Bug was a niezhai—a “debt of evil”—the illegitimate child of parents who’d been sent down to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution, and he didn’t have a real home of his own in Shanghai.

Once, we had to go to Xining to play a few gigs, and this put Bug in especially high spirits. He hopped down the street as if he were performing his own version of the dance aerobics we all used to watch on TV. Bug had grown up in Xining. He loved the dawn in the Northwest. Sunrise there was more luminous than anywhere else, he said.

On the train to Xining, Bug told me story after story about a friend of his in the Northwest. The friend was called Bailian, “white face,” like the villains in Chinese operas.

Everything in northwestern China was gray, everything except the sky, which was the bluest blue. I met Bailian, who turned out to be not much older than we were. His face was indeed very pale, but I was surprised that someone who had a reputation for having been in so many fights should be so good-looking. He had very dark, vacant-looking eyes and close-cropped, slightly wavy hair. I noticed that he had unusually tiny feet. He invited Bug and me to go to a dance hall with him.

It was 1987, before there were any discos. There were just dance halls where people could go to waltz and fox-trot, people of all ages. Dance halls in the Northwest were disorderly places, and competition over dance partners often ended in brawls. This struck us Shanghainese as a real novelty.

That night Bailian had a girl with him. She had a classical kind of beauty and appeared to be even younger than I was. Right in front of us, Bailian turned to Bug and asked him to trade partners. I didn’t like this. If he wanted to dance with me, he could damn well ask me directly. Northwesterners acted very differently from us Shanghainese, I noted. But Bug happily agreed to his request, and I decided that I should give Bug some “face” and not embarrass him.

The song Bailian and I danced to was “Auld Lang Syne,” and everyone there was dancing very carefully and correctly, as if this were the door to a new life.

The day after our second gig, Bailian came over alone and asked me to go out dancing with him, just the two of us. I said, Why are you asking me to go dancing? And maybe my tone wasn’t very nice, since I was in a bad mood that day because the band leaders did nothing but argue over how the money should be divided up. Or maybe Bailian just misunderstood what I’d said. In any case, I could see that he was angry. He looked at me and said, Why can’t I ask you to go dancing? And I said, I didn’t say you couldn’t ask; I just asked you why. He said, Are you coming or not? I said, Are you nuts? Where do you get off talking to me like that? He repeated, Are you coming or not?

The whole time, Bailian’s tone remained flat and unemotional, and he didn’t raise or lower his voice. No! I said.

When Bailian had come in, I was lying on the bed in my guesthouse room, reading a book of poetry, City People. When I said, No!, I flung the book away.

The next thing I knew, I’d been cut by Bailian’s knife. I didn’t see where he’d taken it from, I didn’t see the blade coming at me, and I didn’t see his hand returni

ng it to wherever he kept it. All I remember seeing was him standing in front of me holding the knife, ashen faced, looking as if he’d pulled a muscle. The really interesting thing was that he wasn’t even looking at me. He was staring out the window.

When he cut me, I went cold all over, and through the pain I was struck for an instant by the sensation that my body was separating from itself, and my spirits soared. Wave after wave of numbness hit me, spreading across my back, my mind went blank, and uncontrollable tears poured from my eyes. I started shaking, and I felt the same way I did when I read certain poems, or sang certain songs, or heard particular stories; but it was even more intense and came on more quickly.

Bailian was asking me, Are you coming?

He still wasn’t looking at me.

Where? I said.

Dancing.

OK, I said, sure. But first let me go to the bathroom and wipe this blood off my arm.

I came back and stood in front of him, and when he raised his head to look at me, the knife in my hand went straight into his gut. After the blade went in, I didn’t pull it out. My father had given me this knife. It was from Xinjiang. I don’t know why my father had given it to me; it seemed just as strange to me as when he agreed to let me quit school. After all, he was an “intellectual.”

Bailian stood in front of me without moving. We both just stood there, looking at each other. His expression puzzled me, but before that feeling could sink in, I realized that I could barely stand. Everything became silent and still, and I broke out in a sweat and felt myself drifting, drifting away.

The authorities showed up. Two knives, two people bleeding. Bug came in as well and stood with Bailian. They stared at me. I didn’t know who had called the police, but they locked me up. The cops in the Northwest are mean, and I figured that since Bailian was a local, I was finished.

Every morning I had to go out to the courtyard with the other prisoners and squat for a while with my hands behind my back in front of a gigantic slogan: “Leniency to those who confess and severity to those who refuse.” The jail was full of weird inspirational slogans, all carved into the walls with something very sharp. I didn’t talk to anyone. I was afraid to talk to anyone. The die had been cast; my fate was no longer in my own hands. I got into the habit of stretching out my black-stockinged legs and looking them over. The black silk stockings that were popular then were all wrong for my age, but the constant self-scrutiny convinced me that I had a great pair of legs.

Bug came to see me. He asked me, What did it feel like when the knife went in?

I thought about it but didn’t say anything. Actually, I thought it felt like stabbing a padded-cotton quilt.

He asked me, Do you have any regrets?

I said, I didn’t know what I was doing. I don’t know why I stabbed him—I just had to do it. It never occurred to me that I’d nearly killed a man. I deserve to be punished. But this place is filthy! There’s piss and shit everywhere ’cause people piss and shit anywhere they please. I feel like my whole body is being overrun with germs, and the food is totally disgusting. Life on the outside is so good, even if you have to live hand-to-mouth.

Bug said, Don’t cry; nothing’s going to happen to you. You’re not even eighteen years old; it’s not right for you to be locked up like this. I’ve been to see Bailian—he’s out of the hospital already, and he wants to help you. You’ll be out of here soon.

On the train back to Shanghai, for the first time in my life I experienced the feeling of freedom that birds must have, and it was as if I was finally coming to understand and appreciate the true meaning of freedom. I had this sense that my life was about to become very interesting and exciting. For a long time I gazed out the train window, and the limitless expanses of the plains were like my heart, and the leafless branches on the bare trees traced my mood. The world was so vast! And in the night, as the train bore through the darkness, I loved its sound, and I wrote these lines of poetry in my notebook:

Taking flight

I show the world

my extended wings.

Suddenly I found myself filled with affection for Bailian, and as I thought about how much I liked him, his bright face was shining there beside me, and a curious state of mind came over me. Maybe I was attracted to Bailian because he had in him something that I completely lacked. Being around him had given me a rush, as if I were soaring. I felt completely taken out of myself, so that thinking of him made me tremble all over. I wrote him many letters, but I never sent any of them. And after Saining and I got together, I didn’t think about Bailian anymore.

Sometime later I heard from Bug that Bailian had been sentenced to more than ten years in prison for robbing ancient tombs. But his sentence was commuted, and when he got out he opened up a small business somewhere in the Northwest.

On that afternoon ten years later when I was burning my letters, I rediscovered these pieces of my past. And touching that lucky little scar on the back of my right arm, I savored once again the feeling of the knife going into him, like the experience of a limitless void. It didn’t feel like something that I had actually done myself. And when I caught the scent of those letters, it was just like the scent of youth.

D

1.

His full lips were on my breasts. He was the first man to kiss my breasts; he had made me this picture, given me this picture I loved. When I touched his hair, he quickly undid my clothes, and his tongue made my heart skip. He moved me, and I stroked his hair. His hair was so beautiful!

But when he pulled my body underneath him, I felt myself go suddenly cold. I wasn’t even completely undressed, but in a moment he was inside me. It hurt a lot. Just like that, he had shoved his penis into my body. I lay motionless, the pain boring up into my heart, and I was mute with pain, unable to move.

His hair smelled sweet, and with half of it swaying over either side of my body, there seemed to be two of him moving on top of me, faster and faster, as if he couldn’t stop, and it went on and on for a very long time, and it hurt so much I no longer even knew where my body was.

He wasn’t using his tongue on me anymore, and I felt let down. Except for the noise of his ever-quickening breathing, he didn’t make a sound until it was over, and the whole thing seemed so ridiculous that I was overcome with sadness.

Finally he pressed his whole body against me for the first time and kissed me on the mouth. Until then, that bastard hadn’t even kissed me on the mouth. And then he smiled at me, his full lips curving up, his eyes twinkling sweetly. In that moment, his face became once again the face I’d seen at the bar, a face that was nothing like the face he’d worn when he was fucking me.

I said, You’re the first guy I’ve ever been with. You fucked me. I had my eyes open the entire time and I watched you rape me. You were in such a hurry you didn’t even bother to take all your clothes off.

He said nothing. His long hair was lying across my body, and he didn’t move. The male singer on the CD kept singing, and the sound of his voice was the caress my skin was still waiting for. The simple rhythms kept spinning forward, and the world became smooth and flat inside the music. I didn’t understand a word he sang, but the keyboard was like a vampire, sucking away my feelings.

I have to go to the bathroom, I said. I’m a mess, thanks to you.

I sat on the toilet and looked at his bath towel, and I don’t know how long I sat there, but I felt as though my sex had been seriously injured. The face I saw in the crooked mirror was an ugly face. Never in my life had I felt so disgusted with myself. And ever since, I have carried the shame of that moment in my body.

The music playing on the CD that day was the Doors, and the brutality of the music seemed somehow connected to the brutality of my crude “wedding night,” which violated the sexual fantasy I had held on to for many years. I didn’t dare look at this man’s penis, but I liked his skin, and his lips were very soft, and his tongue could put me into a trance. I didn’t understand the strange agitation in his face, and I

couldn’t find anything there to fulfill the needs of my imagination. The girl that he held in his arms was like a kitten that was too miserable to cry.

I was nineteen. He buried me in pain, covered me with an unfamiliar substance, rude but authentic. Clutching my breasts, he moved in and out, in and out of the hole in me, and I couldn’t see his expression, and no one will remember the way I looked that night, the night I lost my virginity. The self that drained out of my body was a nullity. As I tried to soothe my dazed body, the hazy mirror reflected my empty features back to me. He was a stranger, we had met at a bar, and though the ocean waves in his eyes were familiar, I didn’t know who he was.

2.

That bar was painfully tacky and blazing with yellow lights that shone brightly on every sleazy detail. Sitting at the bar, I was as blank and luminous as the full moon. It was the first time I’d ever sat at a bar, and I felt a little nervous. Every now and then I’d turn and glance this way or that, making it look as if I were waiting for someone. I didn’t even know that I was in a bar. I had only just arrived in this small city in the South. It was 1989, and in Shanghai, where I’d come from, there still weren’t any bars, just a handful of small, unofficial street-side cafés. Maybe those tiny restaurants had bars, but I’d never set foot inside one.

Outside, it was raining hard, but I don’t remember what music was playing in the bar. And I don’t remember when I first caught sight of him, a tall boy swaying back and forth and smiling at nothing in particular. He was wearing an oversize white T-shirt and printed corduroy pants. The pants were wide enough to be a skirt, but they really were pants. He was there in the bar, all alone, rocking from side to side, with a whiskey glass in his left hand and his right hand dancing in the air. I watched his legs as, step by step, he moved toward me. His light blue sneakers had very thin soles, and it looked as if he was tripping over his own feet. His hair was long and straight and glossy, the tips brushing his upper back, and his face was very pale. I couldn’t make out his features, but I was certain that he was smiling, even if I couldn’t tell whether or not he was looking at me too.

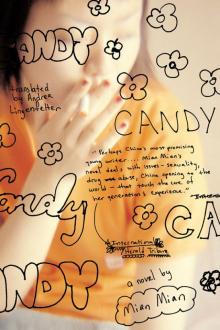

Candy

Candy