Candy Read online

Copyright © 2003 by Shen Wang

Translation copyright © 2003 by Andrea Lingenfelter Reading group guide copyright © 2003 by Mian Mian and Little, Brown and Company (Inc.)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

First English-Language Edition

Little Brown & Co.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com.

First eBook Edition: April2000

The Little Brown & Co. name and logo is a trademark of Hachette book Group

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN 978-0-316-05553-6

Contents

AUTHOR’S NOTE

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

TRANSLATOR’S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE TRANSLATOR

“Mian Mian’s realm is one of wretched love affairs, hard drugs, promiscuous sex, and suicide. Her work is revolutionary for the People’s Republic, and her own tale is one of personal liberation, excess, and redemption.”

— GARY JONES, Sydney Morning Herald Magazine

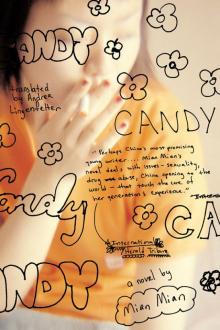

AN INTERNATIONAL LITERARY SENSATION —now available for the first time in English translation—Candy is a harrowing tale of risk and desire, the story of a young Chinese woman forging a life for herself in a world seemingly devoid of guidelines.

Hong, who narrates the novel, drops out of high school and runs away at age seventeen to the frontier city of Shenzen. She falls into a relationship with a young musician, and together they dive into a cruel netherworld of alcohol, drugs, and excess, a life that fails to satisfy Hong’s craving for an authentic self, and for a love that will define her.

Mian Mian’s fresh, strident, and brutally honest voice illuminates the anguish of an entire generation. This startling novel is a blast of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll that opens up to us a modern China we’ve never seen before.

NEW IN PAPERBACK * GREAT FOR READING GROUPS

BROWNSVILLE

Stories by Oscar Casares

“A fine debut. . . . Probing underneath the surface of Tex-Mex culture, Casares’s stories, with their wisecracking, temperamental, obsessive middle-aged men and their dramas straight from neighborhood gossip, are in the direct line of descent from Mark Twain and Ring Lardner.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Oscar Casares does for Brownsville, Texas, what Eudora Welty did for Jackson, Mississippi.”

—TIM GAUTREAUX, author of Welding with Children

SUPER FLAT TIMES

Stories by Matthew Derby

“Imagine The Matrix, but funny, or a neurotic Metropolis, and you might get some sense of what this weird, beautifully written book, made by someone who has watched far too much television, does to your brain.”

— NEAL POLLACK, author of The Neal Pollack Anthology of American Literature

“A vital and astonishing writer. . . . Matthew Derby stages a brilliant wagon circle around everything dull and earthbound in American fiction.”

— BEN MARCUS, author of Notable American Women

Available wherever books are sold

NEW IN PAPERBACK * GREAT FOR READING GROUPS

HOUSE OF WOMEN

A novel by Lynn Freed

“Irresistible. . . . An unusual and unusually satisfying novel.”

—KATHRYN HARRISON, New York Times Book Review

“House of Women is surprising and inevitable, often in the same sentence. It illuminates and, at the same time, deepens the human mystery. I don’t ask for more from a book.”

—MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM, author of The Hours

THE DRINK AND DREAM TEAHOUSE

A novel by Justin Hill

“Justin Hill knows China inside out. Every sentence is filled with knowledge, affection, and a poignant sense of loss.”

—CAROLYN SEE, Washington Post

“Hill understands, like Tolstoy, that human nature cannot change along with the times. . . . This is a book of exoticisms, intoxicated by the human landscape of the Far East, a place of firecrackers and lotus roots. . . . A first novel filled with sensual delight.”

— EDWARD STERN, Independent on Sunday

Available wherever books are sold

NEW IN PAPERBACK * GREAT FOR READING GROUPS

THE BLACK VEIL

A memoir by Rick Moody

“Compulsively readable. . . . A profound meditation on madness, shame, and history. . . . One of the finest memoirs in recent years.”

—JEFFERY SMITH, Washington Post Book World

“Ferociously intelligent, emotionally unsparing. . . . Verbal invention capers and sparkles on every page.”

—DAVID KIPEN, San Francisco Chronicle

SIMPLE RECIPES

Stories by Madeleine Thien

“Simple Recipes introduces a writer of precocious poise. . . . The austere grace and polished assurance of Thien’s prose are remarkable. . . . The trajectories of Thien’s stories are unpredictable; though her characters dream of following simple recipes, they are themselves undeniably original creations.”

—JANICE P. NIMURA, New York Times Book Review

“This is surely the debut of a splendid writer. I am astonished by the clarity and ease of the writing, and a kind of emotional purity.”

— ALICE MUNRO

Available wherever books are sold

FOR ALL OF THOSE FRIENDS WHO HAVE VANISHED WITHOUT A TRACE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I created my own sweetheart, watching him move closer and closer to me. His undying fragility is his undying sweetness and beauty. This book represents some of the tears I couldn’t cry, some of the terror behind my smiling eyes. This book exists because one morning as the sun was coming up I told myself that I had to swallow up all of the fear and garbage around me, and once it was inside me I had to transform it all into candy. Because I know you will be able to love me for it.

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

Most of the action in Candy is divided between the author’s native Shanghai and the enterprising boomtown of Shenzhen, in Guangdong Province. While Mian Mian mentions Shanghai by name, she refers to Shenzhen only as “the South.” Once little more than a farming and fishing village on the train line linking Hong Kong and Guangzhou, Shenzhen began its radical transformation in 1980, when Deng Xiaoping, then China’s premier, proclaimed it a Special Economic Zone (SEZ). Created as a response to the economic stagnation of the Maoist era, the SEZs were integral to Deng’s economic reforms. In contrast to the central planning and state-controlled enterprises that characterized the rest of China, the SEZs were set aside as free of state control. The relaxation of state control and the relative freedom soon created a frontier mentality, and many forms of vice and corruption came to flourish alongside more legitimate private enterprise. Prostitution, drugs, and organized crime, which had been suppressed to a remarkable degree in post-1949 China, thrived in laissez-faire Shenzhen. At the same time, the influx of investment from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the West was accompanied by a flood of cultu

ral influences.

The personal and economic freedom represented by Shenzhen was extremely attractive to many young people all over China, and Mian Mian’s protagonist, Hong, is no exception. In the rest of China, job seekers waited to be assigned a job by the government, which had the right to send people anywhere in the country. Often, people ended up in jobs hundreds of miles away from their hometowns, but they had little choice in the matter. Qualifications counted for something, but a recent high school or college graduate’s display of devotion to the Communist Party was often also a key factor in securing a desirable assignment. In running away to the SEZ to try to make their own way, Hong and others like her were dropping out of this overly constraining system.

What may be remarkable to readers familiar with the last half century of Chinese history is how small a role the Communist Party plays in the lives of the characters who people Mian Mian’s book. The omission is telling. The world portrayed in Candy is just one more reflection of what Orville Schell, in his lively and insightful book Mandate of Heaven, refers to as China’s “gray” culture, one devoid of the “redness” that characterized the Communist culture of the first four decades of the People’s Republic. “Gray” culture is apolitical on the surface but fascinated with gangsters and other outlaws. Its cynicism, irony, and seeming disengagement from politics have a great deal to say about Chinese society today. Whether it amounts to a loss of hope for political change in China or a subtle but effective form of subversion remains to be seen.

A note on currency: The Chinese currency is called the yuan. (There are roughly 8.25yuan to the U.S. dollar.) There are ten mao (or jiao) to each yuan, and ten fen to each mao.

A note on language: Mandarin is the official language of the People’s Republic of China. It is used in broadcasting, schools, and other official settings. However, in private life many people are more comfortable using the native dialect of their home region, such as Shanghainese or Cantonese.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First, I must give heartfelt thanks to my father and mother. My father is my hero. What’s more, he never stopped saying: “She’s a good kid—she just loses her way every now and then.” My mother has this to say: “I am grateful to God for giving me this child. What she writes is so beautiful.”

I also wish to thank my agent William Clark for helping me bring this book into print. I haven’t been to America, but he has made me long to see it. My editors at Little, Brown, Judy Clain and Claire Smith, have been enthusiastic about publishing this book from the start, and I am deeply grateful to them.

Thanks to all my friends, as well. Thank you, Caspar, Tina Liu, Coco Zhao. All of you have given me the strength to love this world and have taught me that darkness always ends in light.

Thanks also to Jim Morrison, Radiohead, and PJ Harvey. Their music has brought its deeply loving caresses into my life.

And last but not least, I wish to thank “my poor George.” He is the King, and my best friend. I can never be hurt again by any kind of love.

TRANSLATOR’S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A big thank-you to William Clark, who called me out of the blue one day and brought me into this wonderful project. From start to finish, he was always there when I needed him. Thank you to our wonderful and indefatigable editors at Little, Brown, Judy Clain and Claire Smith.

Thanks to Josh Salesin for the list of effects, and to all of the friends and friends of friends who gave me pointers on everything from raves in China to medical info. Thanks to my readers, Davi Grossman and Chris Sanford. Your comments on the early drafts of this translation were invaluable.

I wish to express my gratitude to the late Jeri Wadhams, who gave me my first opportunity to read Chinese literature and pointed me down the path I have taken. And I will always be grateful for the generosity and dedication of Mrs. Ping Hu, who taught me the Chinese language, and Dr. William Tay, who inspired me to explore the complexity of modern China.

Lastly, I give my undying love and gratitude to my family—to my husband, David, whose patience and gentle nature sustain me even in stressful times, and my children, Oona, Isaiah, and Eleni, who fill my life with their sweetness, their love, and their brimming imaginations.

A

Why did my father always have to push me in front of the Mona Lisa? And why did he always make me listen to classical music? I suppose it was just my fate, for want of a better word. I was twenty-seven years old before I finally got the courage to ask my father these questions—up until then, I couldn’t even bring myself to utter the woman’s name, I was so terrified of her.

My father answered that Chopin was good music. So when I was bawling my head off, he would shut me in a room all by myself and have me listen to Chopin. In those days none of our neighbors had a record player or a television the way we did. What’s more, many of them were forced to subsist on the vegetable scraps they scrounged at the market, since meat, cloth, oil, and other basics were still being rationed. My father thought that as a member of the only “intellectual,” or educated, family in our entire apartment building, I should feel fortunate.

Father said that it had never occurred to him that I might be afraid of that print hanging on our wall. Why didn’t I just look at the world map that was hanging right next to it? Or the map of China? Or my own drawings? Why did I have to look at that picture? At length he asked, Anyway, why were you so afraid of her?

Many other people have asked me this very question, and each time someone asks, I feel that much less terrified. Still, it’s a question I can’t answer. Just as I can’t explain why, from the time I was a very small child and barely able to talk, my father would have chosen to deal with my crying the way he did.

I have never actually taken a good close look at that woman (I’m far too afraid of her to attempt that). Nonetheless, my most powerful childhood memories are of her portrait.

As I grew older, certain ideas became fixed in my mind. Her eyes were like a car crash at the moment of impact; her nose was an order issuing from the darkness, like a ramrod-straight ladder; the corners of her mouth were cataclysmic whirlpools. She seemed to have no bones except for her brow bones, and those bald brows were an ever-present mockery. Her clothing was like an umbrella so massive that it threatened to steal me away. And then there were her cheeks and fingers. There was no denying that they resembled more than anything the decaying pieces of a corpse.

She was a dangerous woman. And I was often in this dangerous presence. I had very few fears, but she terrified me. In middle school history class, I was once startled to look up and find myself face-to-face with a slide projection of this painting. My throat tightened, and I cried out in shock. My teacher reacted by concluding that I was a bad student and making me stand up as punishment. Then he took me to see the assistant principal, who gave me a stern lecture. At one point they went so far as to accuse me of reading “pornography,” like the then-popular underground book The Heart of a Young Girl.

That was the beginning of my hatred for the man who had painted her. And I started to despise as well all those who called themselves “intellectuals.” My hatred had a kind of purity about it—I would open my heart and feel a convulsive anger pulsing in my blood. I named this sensation “loathing.”

My unalloyed fear of this painting stripped away any sense of closeness I might have felt toward my parents. And it convinced me, all too soon, that the world was unknowable and incomprehensible.

Later I found the strength to deal with my fear. I found it in the moon and in the moonlight. Sometimes it was in rays of light that resembled moonlight, and sometimes I saw it in eyes or lips that were like moonlight. At other times still it was in the moonlight of a man’s back.

B

When it rains I often think of Lingzi. She once told me about a poem that went: “Rain falling in the spring, / Is heaven and earth making love.” These lines were a puzzle to us, but Lingzi and I spent a lot of time trying to unravel various problems. We might be trying to figure out germs,

or the fear of heights, or even a phrase like “Love is a fantasy you have while smoking your third cigarette.” Lingzi was my high school desk mate, and she had a face like a white sheet of paper. Her pallor was an attitude, a sort of trance.

Those days are still fresh in my mind. I was a melancholy girl who loved to eat chocolate and did poorly in school. I collected candy wrappers, and I would use these, along with boxes that had once contained vials of medicine, to make sunglasses.

Soon after the beginning of our second year of high school, Lingzi’s hair started to look uneven, with a short clump here, a longer hank there. There were often scratch marks on her face. Lingzi had always been extremely quiet, but now her serenity had become strange. She told me she was sure that one of the boys in our class was watching her. She said he gave her steamy looks—steamy was the word she used, and I remember exactly how she said it. She was constantly being encircled by his gaze, she said. It made her think all kinds of unwholesome, selfish thoughts. She insisted that it was absolutely out of the question for her to let anything distract her from her studies. Lingzi believed that this boy was watching her because she was pretty. This filled her with feelings of shame. Since being pretty was the problem, she had decided to make herself ugly, convinced that this would set her back on the right path. She was sure that if she were ugly, then no one would look at her anymore; and if nobody was looking at her, then she could concentrate on her studies. Lingzi said she had to study hard, since, as all of us knew, the only guarantee of a bright future was to gain admission to a top university.

Throughout the term, Lingzi continued to alter her appearance in all kinds of bizarre ways. People quit speaking to her. In the end most of our classmates avoided her altogether.

As for me, I didn’t think that Lingzi had been that pretty to begin with. I felt that I understood her—she was simply too high-strung. Our school was a “key school,” and it was fairly common for a student at a school like ours to have a sudden nervous breakdown. Anyway, it wasn’t clear to me how I could help Lingzi. She seemed so calm and imperturbable.

Candy

Candy